Peoples Choice Award

The People’s Choice Award invites all visitors to the M16 Artspace Drawing Prize to cast a vote for their favourite artwork. The winner will be announced on social media at the close of the exhibition.

The recipient of the Peoples Choice Award will win a $500 voucher generously sponsored by The Framing Store.

Revisit the Drawing Prize finalists below and cast your vote at the bottom of this page.

Finalists - M16 Artspace Drawing Prize 2025

Submerged / Exposed, 2025

Watercolour monotype on paper, 76 x 56 cm

Submerged / Exposed is my response to a significant learning experience, participating in the ANU Environment Studio's 2025 Sharing Stories field program on Walgalu Country. The generous Walgalu/Wiradjuri artist, Aidan Hartshorn led a group of creatives through the Tumut region, sharing personal insights and prompting discussion about the ongoing impact of the Snowy Hydro Scheme on Walgalu Country and cultural sites. He also demonstrated the foundational practice of making stone tools and we gained awareness of the presence of worked stone as we walked. This was particularly striking where the controlled flow of the Tumut River had caused water levels to drop and a recently submerged landscape to be exposed. I thought about that submerged landscape, revealed and concealed, while flooding my monotype printmaking 'plate' with fluid watercolour paint. I then worked back and forth to define the roots of a severed eucalypt enmeshed in the stony river bank. This involved lifting out light, with a damp cloth wrapped around my fingertip, and building up shadows with a brush.

Image courtesy of Brenton McGeachie.

The last before, 2025

Holes punctured in found wall, variable dimensions.

This work is a poem punched into the wall, which reflects on a moment of intimate care – slow, tender, unnoticed. This work honours the kind of labour many women carry: emotional, unpaid, often invisible and routinely excluded from data-driven narratives.

The work changes depending on the distance at which it is read. As the viewer moves closer the words slow and the reader is held there as each word forms.

Bloat, 2025

Gesso, ink, pigment powder, 90 x 75 cm

bloat

Verb

to become swollen with fluid or gas

That feeling of being on the verge of bursting. My stomach aches, stretched by grief in all its flavors. I try to decompress by chasing ideas: some new, some only half-formed, some already lost. Lately, the art I make feels ugly, as if I’ve hurled every shade of emotion onto the canvas, unsure if any of them belong. I’m frantic; unthreading the seams of what was and what is, just to relieve the pressure.

Drawing has always been a kind of home, a place without a map, an outcome unknown. Each mark simmers in me before it rises, like heat trapped deep in the gut, waiting to boil over, waiting to become.

This work is made in collaboration with vibrators suspended from the ceiling. As I move the canvas against these vibrating instruments, unexpected textures and marks emerge gestures I could never control, only invite.

Image courtesy of Brenton McGeachie.

The artist sleeps, 2025

Coloured pencil on paper, 200 x 150 cm

The Artist Sleeps is a drawing that explores the vital role of rest and renewal in the creative process. Creativity is not constant, it moves in cycles, flowing between productivity and dormancy. When wakefulness blurs into dreaming, the artist retreats to gather strength, sifting through subconscious visions in order to develop new forms.

Sometimes she awakens with clarity, emerging with work fully formed, radiant and ready. At other times, she lingers on the threshold between dreaming and rising, drifting where reality and introspection converge. Sometimes the dream becomes a nightmare, birthing something through pain. In these moments, creation arrives not as a whisper, but as a rupture, a scream from the chest, raw and unfiltered. This drawing is a meditation on that in-between state. It reflects on the necessity of rest, the madness of the world we wake into, and the transformative potential of dreaming. As the artist stirs, so too does the work, rising from the depths with truths only sleep could summon. To witness is to participate, to step into the quiet tension between rest and emergence, and to consider your own place in the unfolding of an artist’s vision, whether awake or in her dreams.

Emma Michaelis is an artist who has rested long enough.

Image courtesy of Brenton McGeachie.

Babydolls (David Street, Marrickville), 2024

Watercolour on Yupo, aluminium, acrylic polyurethanem, 110 x 60 x 48 cm each

Imogen Eve Rowe paints watercolours of gardens and other subjects that capture her attention, using an observational practice to explore themes of community, belonging, and identity.

In this work, Rowe depicts two putti, naked, supernatural baby boys playing instruments, positioned on either side of a footpath in a local subtropical front yard. Her choice reflects a fascination with the persistence of religion, fairytale, and historical iconography that continue to shape and hold influence within Australian suburbia.

Can't get you out of my head, 2025

Mixed media on paper, 105 x 157.5 cm

Jenny Herbert-Smith’s recent work emerged during a drawing workshop in a vast industrial space in Portland, NSW. Working directly on the floor, she instinctively expanded the scale—taping together multiple sheets of paper in response to the open architecture and the physicality of the space. As a sculptor, Herbert-Smith is accustomed to working in the round, and she brought that same spatial awareness to drawing: circling the work, responding intuitively to mark, texture, and rhythm.

The process was entirely exploratory. With no fixed plan, she allowed the drawing to evolve through movement and gesture. A head-like form—suggestive of a skull—surfaced unexpectedly. Though unplanned, it quickly captured her attention. After setting the piece aside for several months, she returned to it and found the skull had become central—unavoidable in both presence and symbolism.

The work, titled Can’t Get You Out of My Head, references a track by Electric Light Orchestra that played often during its creation. More than a nod to the soundtrack, the title speaks to the image’s persistent, almost haunting presence.

Herbert-Smith’s practice explores the shifting boundary between abstraction and figuration. She uses drawing as a space for bodily engagement and intuitive response, privileging process over outcome. Whether working in sculpture or works on paper, she remains deeply interested in how form emerges—slowly, unexpectedly—through physical interaction with materials.

Image courtesy of Brenton McGeachie.

Familiar Territory, 2024

Blown glass, sandblasted and engraved, 56 x 29 x 29 cm

This blown-glass amphora becomes a vessel for drawing: a translucent surface where engraved lines translate the language of architecture into luminous form. Historic façades from Adelaide provide the imagery, yet the work speaks more broadly to the human impulse to gather, learn, and belong.

Architecture does more than provide shelter. The right design can turn strangers into neighbours, creating places where people feel welcome, safe, and engaged. Museums, libraries, universities and community centres hold the memories of those who pass through them, shaping how societies meet and how futures are imagined.

Across these etched cityscapes appear small figures absorbed in their smartphones, taking selfies, texting and capturing fragments of experience. Their presence reflects how digital technology now mediates community life: buildings once reliant on face-to-face encounters are simultaneously shared and re-experienced through screens, extending their reach while altering how connection is felt.

Glass, at once fragile and enduring, underscores these dualities. The classical amphora form references vessels as keepers of culture, while the engraved drawings bring that tradition into the present, mapping the bonds between people, place, and the ever-evolving ways communities communicate.

The Tunnel/Heart of Darkness, 2024

Coloured pencil on paper, 197 x 150 cm

This large pencil drawing is of the entrance to an earth tunnel in the village of Darwan, Afghanistan, from an image taken by Australian SAS soldiers during twenty years of War in Afghanistan.

I have returned the image to a scale around life-sized, looking for traces of its history: place as witness.

The choice of coloured pencil as material is a deliberate decision to insert the perspective of children back into narratives of war.

Image courtesy of Brenton McGeachie.

Vague Grey Cloud, 2024

Single-channel HD video with sound; colour, 00:05:57

Fragmented rudimentary hand-drawings sourced from notes and sketchbooks form the basis of abstract moving image, Vague Grey Cloud. The selected drawings are ‘auditioned’, but their potential is ambiguous until they enter the digital realm. Working through a process of intention and chance, the narrative continuously shifts as I am guided by the transformative qualities of drawing for choreographed sequences of archetypal imagery, amorphous forms, and remnants of decayed structures. The transparent cube, a recurring motif in my work, speaks of fragility and resilience in the face of adversity and the unknown. Ultimately, the once disregarded, with care, becomes elevated with new meaning and power.

In every whisper and echo of eternity, 2024

Found plastic and cotton thread, 45 x 50 cm

Kirsten Farrell is a conceptual artist currently focussed on the materiality and ontology of plastic. In every whisper and echo of eternity is representative of their of the last four year years, in which they primarily use found plastic and cotton thread to construct two(-ish) dimensional works that propose a radical re-evaluation of human relations to plastic. This work does not easily fit into a category of art medium but spans textile, collage, painting and drawing.

In every whisper and echo of eternity cotton threads have been repetitively, obsessively drawn through layers of plastic. It is a very slow manner of making in which the lines of the thread iterate and build layers. Through the iterative construction the composition emerges gradually, each line informing the next in relation to the ground, a super slow drawing process. This process both preserves the transparencies of the plastic and through the iterative lines changes its state to a shimmering crinkly surface that layers the colours of the plastic with the colours of the threads. It contains fundamental elements of drawing: linearity, time and material yet actively challenges its boundaries.

The slowness of the work connects to the deep time contained in plastic, drawn from ancient petrochemicals. The works meditate on the this deep time and propose a more thoughtful knowing of the material.

Image courtesy of Brenton McGeachie.

Aral Sea, 2001 (diptych 9), 2025

Oxide, spent ferric chloride, ink, gum arabic on Hahnemühle paper

106 x 156 cm

This drawing is an elegy to the artist’s late father and to the Aral Sea, a vast inland sea in Uzbekistan that has almost completely dried up due to Soviet mismanagement. The resulting salinity crisis is an environmental catastrophe. Having worked with salinity in the Murray Darling Basin, Hall’s father was involved in attempts to remediate the Aral Sea. Using imagery from photographs taken there 20 years ago, the work speaks to a sense of absence within the landscape and to the expanse of loss; as a concept spanning both time and place, both personal and collective. The work utilises oxides, spent ferric chloride, ink and gum arabic which react and resist with each other to build layers of marks.

Image: Stephen Best

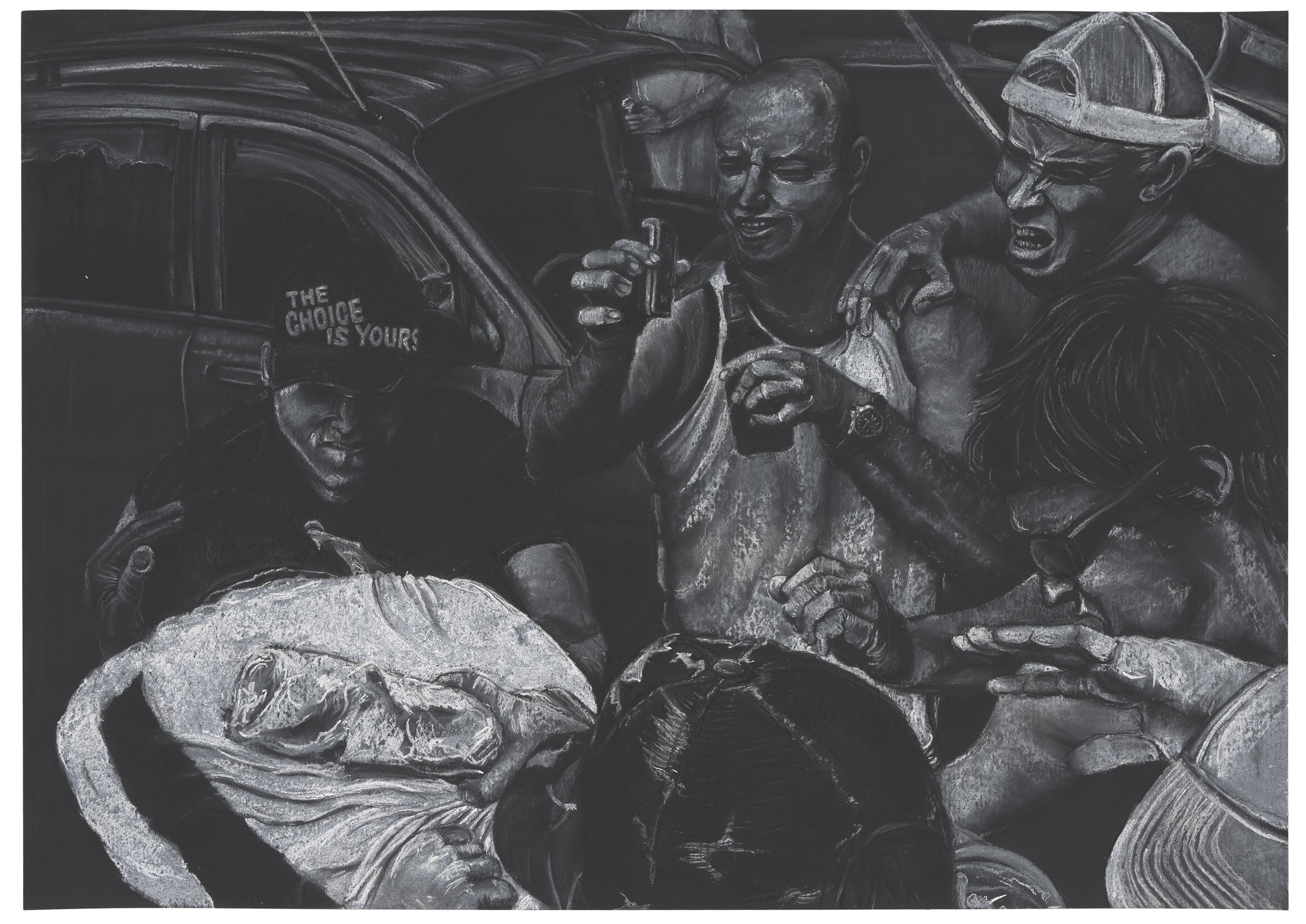

Cronulla riots 2005, 2025

Chalk on black paper, 59.5 x 83 cm

Matthew is a First Nations artist and was inspired to create this picture of the 2005 Cronulla riots following a recent protest against immigrants and immigration. He seeks to show how the mindset has not changed. Centuries after the initial colonisation of Australia, we are still targeting minority ethnicities. People who are descendants of immigrants themselves, fighting against those seeking a better life in this beautiful country. When will we learn to see each other as human, rather than the colour or country we were born in. Every single one of us has the right to be recognised as an equal and a life of harmony. This artwork has been created using only black and white chalk, to capture the essence and energy of the scene.

Image courtesy of Brenton McGeachie.

FRAGILE - This Way Up, 2025

Washi tape and acrylic on cardboard, 194 x 194 cm

FRAGILE - This Way Up was created by Merryn Trevethan as a way of processing conflicting feelings of dislocation and privilege experienced during her relocation to Melbourne following more than a decade living in Asia. Created on redacted shipping boxes, the artist draws with tape, creating a network of interconnected lines, some of which are unexpectedly cut-off referencing the dislocation of leaving unfinished business behind. The drawing has been cut into blocks and is presented like a Sliding Block Puzzle. One piece has been removed and the blocks rearranged, asking the question “How do I put the pieces back in the right order?”. The work also acts as a rumination on the burden and privilege of “stuff”. Having shipped her possessions, including studio equipment and artwork accumulated during her time as an “expat” to her former home in Melbourne, Trevethan explores the overwhelm of moving countries- multiple times and the challenges of trying to fit back in to a home she had left so long ago. She considers what it means to have a choice in where she lives and the freedom of movement that comes with an Australian passport. Throughout this experience, Trevethan examines the immense privilege of being able to return to a country free from wars, conflicts and the kind of political strife that many are forced to flee without anything at all. While grateful for these privileges there is a niggling sense of guilt as she tries to put the puzzle back together.

South Arm Tasmania, 2025

Watercolours, posca pens, acrylic on Hahnemühle paper, 80 x 106 cm

I get all sorts of ideas from everyday living, most of these ideas come from the land, the incredible colour, shapes & patterns in everything around, the smells, sounds, & the stories passed down from my elders. With the love from my family, sharing of knowledge, respecting our cultural ways, being part of our family kinship, all this beauty gets put into my paintings as some sort of story. Using line work is our Yuin cultural way, I enjoy playing with colour and using them in a way that uplifts people.

Image courtesy of Brenton McGeachie.

Woman Ignoring Housework, Watching the World Implode, 2025

Hand embroidery, free motion sewing machine drawing, cotton appliqued and pencils on cotton, 60 x 50 x 5 cm

In a time of global crisis and relentless information overload, Nicole O'Loughlin explores the tension between action and inertia. Her practice reflects the struggle to remain present while the world feels as though it is spiraling out of control.

This work uses textiles as a form of drawing, layering fabric and thread to construct a domestic scene saturated with colour and detail. A figure sits enveloped in a cascade of household linens, surrounded by books and everyday objects, a space where comfort and chaos coexist. Through stitched lines and tactile surfaces, Nicole transforms ordinary materials into a visual language of resistance and refuge. Each thread becomes a mark, echoing the meditative rhythm of traditional drawing while expanding its possibilities.

For Nicole, drawing with textiles is not passive; it is a deliberate act of reclaiming agency. The process slows the mind, grounds the body, and offers a moment of clarity amid uncertainty. Her art becomes both a response and a refuge, a way to engage with the world while holding onto something tangible and true.

Image courtesy of Brenton McGeachie.

Sweet Pots, 2025

Ink, pastel, acrylic, pencil on paper, 96 x 74 cm

Over the past few years, I’ve been creating facsimiles of handwritten notes I've found in public spaces. I’m drawn to their speculative nature—the mystery behind who wrote them, and why—as well as the unique handwriting and the wear each piece of paper carries. By replicating them as large-scale drawings, I turn these small, ephemeral objects into monuments that invite closer scrutiny and interpretation. Even the most banal note can offer insight into the human condition, reveal overlooked stories—or like 'I am not a bin'—suggest double meanings.

Swallow Nests FG, 2025

Charcoal, coffee, collage and spray paint on 12 sheets of paper, 200 x 200 cm

The work I make may appear abstract, but it all starts with drawings made in the landscape and then the forms are filtered through various media to disrupt and force a visual transformation and this in turn creates questions about how we see ourselves in nature. These particular drawings were made under the verandah of a house at Fowlers Gap Research station in Western NSW, looking at a variety of swallow nests.

Image courtesy of Brenton McGeachie.

A page from an incidental biography, 2024-2025

Colour pencil on found paper, steel shelf, 120 x 180 x 7 cm

A page from an incidental biography (2024–25) is a series of drawings on recycled envelopes sent to the artist from various superannuation companies, employers and cultural organisations. Collected because they were saved in tax documentation, they are a material trace of living when employed in precarious labour. The drawings reflect Raquel’s movements over a 25-year period between rental properties, lovers and parents’ homes to her most recent address, a place she owns in Canberra. While they form a kind of biography her life, they are emblematic of the ways that creatives continue to live in and move between other people’s houses. Some of the texts on the drawings refers back to works made early in Raquel’s practice when she was focussing on and alternative forms of living and housing, such as Rental beige (2000) and I used to live here (2001). The use of everyday materials reflects Raquel’s ongoing concern of reflecting the world through a studio practice, her commitment to leaving a light ecological footprint.

Image: David Patterson

Headbowls, 2024 - ongoing

Headbowls is an ongoing project in which Robbie Karmel has made a series of turned segmented wooden bowls designed to be worn on the head and drawn on, printed from, modified, damaged, repaired, performed and reperformed. As participatory and performative objects the bowls are worn and drawn on collectively by the artist and audience.

The Headbowls provide a meditative space to observe, consider, and respond to perceptual experience—the shape and senses of the body, the weight of the bowl, interactions with others, and the tangled activity of drawing.

This iteration of the work presents two headbowls fused at the temple, creating an object that requires a second person to activate or play with. The work aims to embody a request for assistance, to share the weight of the object, and to collaborate in drawing and playing. Conversely, the Headbowls in this configuration are insular and myopic, a closed and potentially competitive or antagonistic engagement, reinforced by the videogame iconography that informs the helmet-ness of the Headbowls.

These objects are an invitation for social production of drawings that are ambiguous in their subject, object, author, and viewer. The collective Headbowl performative drawing invites people to access their tacit embodied knowledge and capacity for mark making and to collectively develop and share that understanding through the activity. These are objects that are played with, drawn on, broken, fixed, modified, pulled apart and put together again, and have no clear state of completion.

Viewers are invited to wear and draw on the Headbowls.

Image courtesy of M16 Artspace.

Processional Way, 2025

Mild steel and micaceous iron oxide enamel, dimensions variable

Rmsina Daniel is an artist concerned with figuration and the human form. Daniel was always interested in the human condition as she firmly believed that the human is the central figure of this world. Daniel is a sculptor capable of working with a different range of materials. Her practice begins with drawing from a coffee cup seeking figures, then further extended through sculpture. Daniel has been working continuously with steel for 6 years. Her residency at the Sydney Olympic Park Armory allowed her to further her skills in welding. Usually, the environment and the site form the scale of her sculptures. Most of Daniel’s works are abstract relief sculptures and involve installation and composition that reveals a certain truth.

Abba and me, 2025

Posca, pigment marker, acrylic paint on canvas, 175 x 160 cm

Steven Patreach has been creating art at Hands On Studio for 29 years, where his vibrant personality and passion shine through every piece he makes. His work is filled with energy, inspired by people around him, the movement of dance, the rhythm of basketball, and the delicate beauty of flowers. These influences come together in a style that is unmistakably his own—full of life, color, and emotion.

Steven’s art is expressive and deeply personal. Each piece tells a story, capturing the joy he finds in motion and nature, and inviting viewers into his world. There’s a warmth and honesty in his work that makes it easy to connect with—it’s art that feels alive.

As a much-loved member of the Hands On Studio community, Steven brings dedication, creativity, and heart to everything he does.

Margaret and Frazer Fair, 2025

Charcoal, 61 x 80 cm

This charcoal portrait by Surya Bajracharya depicts his mother and uncle in their youth, based on a photograph he discovered in a shoebox. The original image had a haunting, cinematic atmosphere, evocative of Diane Arbus or David Lynch, that compelled him to draw it. What began as a straightforward representational drawing exercise gradually evolved into a personal meditation on memory, family, and the passage of time.

Bajracharya uses charcoal, a tonally dynamic, delicate and vulnerable medium to building the portrait through countless tiny, abstract gestures. The result is a life-like, photo-realistic rendering, yet the process itself became far more than an act of reproduction. As he worked, Bajracharya found himself in quiet dialogue with the photograph—contemplating its hidden layers and reflecting on the lives and experiences of the two young figures captured in time.

The act of drawing became a meditative process, one that bridged personal history and artistic inquiry. In shaping the likeness of his family members, he also traced the contours of aging, nostalgia, and the impermanence of memory.

This portrait stands as both homage and investigation—an attempt to hold still a fleeting moment, and to explore how the past lives on through art, memory, and the quiet labour of close observation.

Image courtesy of Brenton McGeachie.

Some Sort of Notation, 2024

Oxidised mild steel and copper, 200 x 200 cm

Some Sort of Notation takes its name from the journals of Alexander Marshack— an archaeologist who, in 1964, published a study on seemingly random, human-made notches on Palaeolithic bones. Adamant that the markings were far from meaningless, he instead proposed that they were complex lunar observations, therefore a proto-writing system. “It is clearly neither art nor decoration,” he’d said, “but some sort of notation.”

This work considers how modern language structures – such as grids, sequences, patterns and repetitions – create illusions of legibility, prompting misrecognitions of language where it mightn’t exist. By affecting how we internally differentiate between image and text, these structures can confuse our transition between looking and reading, opening a space where poetic and erroneous correspondences can occur.

This work weaves connections between the ancient artefact and the science-fictional to continue investigations into the gaps and overlaps between drawing and writing. 'Some Sort of Notation' is an invitation not to decipher, but to misread and to ‘uncode.’ To pull apart, dismantle and unravel the language structures we rely on to resolve feelings of suspicion and duplicity. To draw conclusions, and doubt conclusions; to get lost and disoriented; and to linger in a space where meaning can be glimpsed or sensed, but never fully grasped.

Image: Jessica Maurer

Pigeonometry (beneath the rings of Saturn and sparwled upon the sandy beaches of Titan, I dreamt of a mechanical pigeon messiah), 2025

Cardboard, electronics, found objects, 49 x 20 x 19 cm

Pigeonometryis an experimental kinetic work that combines sculpture and hand drawn animation. Pressing the button activates the wheel which cycles through a small book of hand drawn animation frames. In a world of infinite screens and digital content I have chosen to embrace the hand made. An analog rebellion in the age of infinite screentime.

Image courtesy of Brenton McGeachie.

Chimeric Bloom, 2025

Pen, ink, markers and liquid acrylic on white birch plywood, 120 x 150 cm

In Chimeric Bloom, Tziallas explores the fragile intersection between biology, memory, and the human condition. Drawing from a lifetime of experiences with chronic illness, her work contemplates the body’s capacity for endurance, adaptation, and transformation. The ambiguous organic forms within the composition evoke cellular structures, organs, and botanical life, intertwining in a rhythm that blurs the boundaries between the human body and the natural world.

Tziallas approaches the body as both vessel and landscape, resilient yet ephemeral. Her intricate patterns and use of colour notion cycles of growth, healing, and decay, reflecting the delicate balance between vitality and vulnerability.

Image courtesy of Brenton McGeachie.